Web Scraping and Webcomics

14 Nov 2016 —I like statistical models. I like webcomics. I like not having to suffer through deciding whether a webcomic is ever going to update regularly again. I began to ask myself, “Can I use statistical modelling to tell me when I should stop hoping a webcomic will keep updating?”

Nothing is more haunting than that oft-repeated phrase: “updates when?” It’s not even about the wait, it’s about the uncertainty–either end or start updating, don’t keep me in limbo! I would love it if I could make a model that could just tell me, “Hey, this comic is entering its death spiral, abandon ship!” Also, I just like learning new statistical methods.

Although that model is still in the works, I’ve gotten my hands on a bunch of cool data in the meantime. This post isn’t quite a tutorial; it’s more like a demonstration of how you can fun with simple web scraping and niche interests–but I’ve attached all the code I used, complete with documentation and a flexible design for newbies who want to start collecting their own data.

Web scraping 101

In order to make a model, you generally need data to train it on. Most webcomics don’t have a downloadable R database of all their updates, so you’ll have to get the data yourself. You can click through potentially thousands of pages, recording the dates manually, or you can use web scraping to do it automatically1.

If you use Python and want an incredibly easy-to-get-into web scraping tool, check out the Python module, Beautiful Soup (I used bs4). In a nutshell, it loads HTML pages and parses the elements into a tree automatically. Extracting, say, all the img tags on a page can be as simple as: soup.find_all('img'). Beautiful Soup is pretty simple to learn and the documentation makes it a breeze. Check my source code at the end for the code I used.

Broodhollow updates: a story of an author’s life

“Broodhollow.” The name sounds like a title that a moody fifteen-year-old would come up with, but it is absolutely my favorite webcomic. Ever. Broodhollow’s art is beautiful and the story writing is some of the best I’ve ever read. One part comedy and two parts creeping horror, if the phrase “Tintin meets H.P. Lovecraft” appeals to you at all, go read it right now. If author Kris Straub can finish the comic with a tenth of the talent he’s exhibited so far, I’m confident this will go down as one of the great graphic novels of our generation.

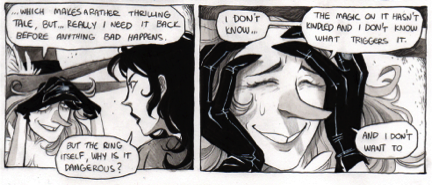

A sample of Kris Staub's genius: Broodhollow.

That is, if he can finish it. Kris is a pretty prolific artist and just had a child a couple of years ago. While he’s continued regular updates to his non-serial comedic strip, Chainsawsuit (another one of my favorites, actually), Broodhollow has gone through a few hiatuses.

The data

So let’s actually look at how often Broodhollow has been updating.

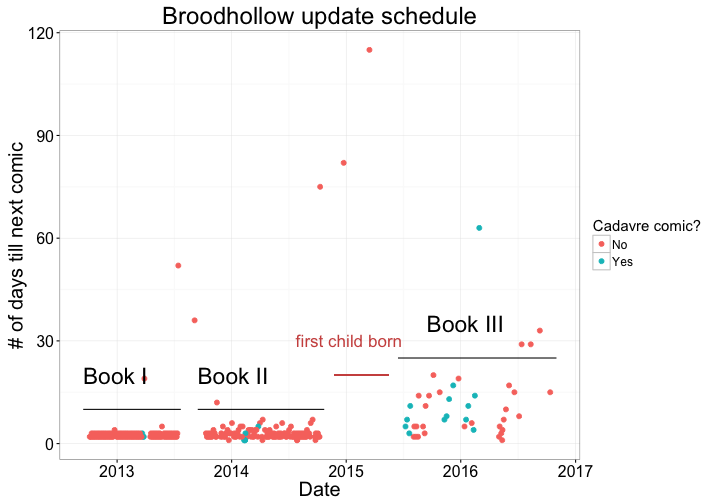

'Cadavre' comics are non-serial humorous strips about the daily life of a French-accented skeleton, generally consider filler material.

I like this graph because it visually tells the story of the evolving involvement of the author with the comic. Book I of Broodhollow, “Curious Little Thing”, has very consistent updates, as evidenced by the tight line of updates. Book II, “Angleworm”, continues after a short rest, and updates are still fairly regular, although you see there’s definitely more variability. But then, BAM! As they say, a baby changes everything. After a long hiatus, Book III teeters to a start, with sporadic updates and lots of filler material.

To me, webcomics that fall into this pattern are the reason why I want a model to tell me if I should give up on them. They keep toying with my hope that they will start updating like they were before. But on the other hand, we can see that even though Book III updates less frequently, Kris hasn’t forgotten about it. We’ll need more data.

SMBC: longer and more uncut

Unlike Broodhollow, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal has no problems with regular updates. In a downright freakish display of perseverance, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal (or SMBC as its often known by) updates every. Damn. DAY. Zach Weinersmith is a gangly, red-headed beast, and if just by virtue of his update schedule, SMBC would remain one of my favorites.

Early SMBC comics usually consisted of a single panel, and relied on a specific brand of humor to get laughs. To long-time readers of the comic, my brother and I, it felt that a while ago Zach started doing longer and longer strips, which we joked got less and less funny. So when I started collected data, my brother suggested that I collect data on how long his strips were at the same time. Were his strips really getting longer, or was it just our imagination?

The data

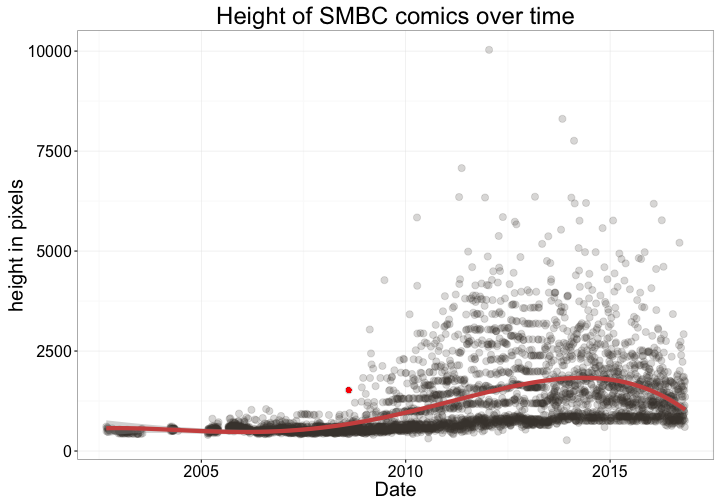

Combining the Pillow module for Python 3 with my web scraping code, I recorded the width and height of each of his comics. Unlike many webcomics, I should add, SMBC generally is in “portrait” orientation, meaning that the longer the comic, the taller the image.

It would seem that around late 2008, (August 10th by my reckoning, marked on the graph) Zach started getting bored with one-panel comic strips.

I was surprised by how quickly SMBC started coming out with longer comics after late 2008. Clearly, once Zach tasted the sweet, sweet taste of multi-panel comics, he couldn’t let it go.

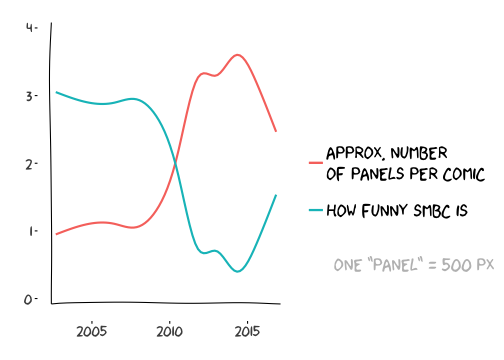

Now, for a little bit of humor only Zach Weinersmith could find funny:

Just kidding Zach! I know how much you appreciate graph jokes.

Typical height of 1 panel ~= 500 px. Ironically, this plot was created with the `xkcd` package in R.

Prague Race: testing a hypothesis

The last webcomic I’ll be discussing here is Prague Race by Petra Nordlund. Prague Race is another pretty comic with great writing and plot.

Prague Race by Petra Nordlund: mostly funny, sometimes dark, and with enough mystery in the background to keep readers guessing

Recently, I’ve gotten the feeling that the author is itching to start on newer projects, and that updates might be coming less frequently. Additionally, I occasionally read the little blurbs she posts with her updates, and formed the impression that after longer delays she would tend to apologize a lot for being late.

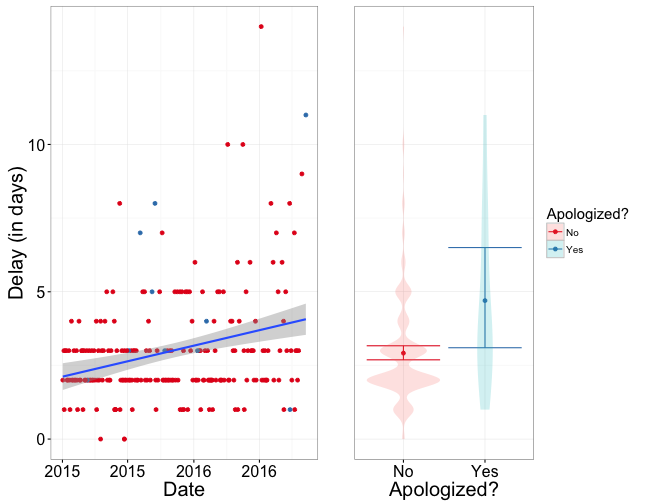

When I was web scraping Prague Race I decided to empirically test these hypotheses: are updates actually coming out less frequently, and does Petra tend to apologize after longer delays?

The data

As a first-order approximation of how much she was apologizing, I collected the number of times the word “sorry” appeared in the update text for each comic. As a first-order approximation of whether the update cycle was slowing down, I’ll be fitting your basic, barebones linear regression model to the data, which I’ll add to the graph below.

It does seem that updates are slowing down slightly, and although updates with the word "sorry" seemingly tend to come after longer delays, there were too few data points to say something definitive. Errorbars represent bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

So how did my hypotheses bear out?

It does seem that updates are slowing down–the date was a significant predictor of delays between updates, with later updates tending to have longer delays. And although the graph might suggest that updates with apologies tend to come after longer delays, the data revealed that she had only said the words “sorry” ten whole times in the entire run of the comic, pretty much invalidating my original feeling that she apologized a lot. Of course, my measure of apologizing was pretty rough, but I am in grad school and I do have more important things to do.

Hopefully you get the sense that web scraping can get you some potentially interesting data without a lot of hassle. If you’re a data-geek or a webcomic enthusiast, check out my source code below and give it a whirl yourself. There’s a lot of untapped data out there, so go out and scrape it!

Source Code:

My multi-thread web-scraper, written for Python 3.4+, requires Beautiful Soup and Pillow. If you have pip you can try: python3 pip install beautifulsoup4 and python3 pip install pillow. This is my first time ever working with threads in Python–probably overkill, but it was fun to learn about. If you have any comments about what I could do better–any rookie mistakes I made–feel free to leave a comment below.

My crappier, non-threaded, web-scraper with poor documentation. Also written for Python 3.4+, requires Beautiful Soup and Pillow. This is the earlier, crappier version of my code for a few of the examples, more or less.

The R Markdown file this blog post is generated from, if you want to know what R code I used for the analysis and plotting.

Footnotes

-

I should point out, for pedantry’s sake, that webcomics make especially easy targets to web scrape, given their fairly consistent structure and general lack of JavaScript. Web scraping is a bit harder when you want to collect JavaScript-generated content–check out

PhantomJSandSeleniumPython libraries for good places to start. ↩