How to Use Plotly/HTML Widgets in Jekyll the RIGHT Way

04 Apr 2020 —Plotly, which lets you interact with data and plots in incredibly pleasing ways (see this post by my brother and I for examples) offers a load of cool possibilities with R, whether you want dashboards or engaging data visualizations. It’s super web-friendly and fits like a glove into workflows that knit HTML.

The only problem is that you’re basically screwed if you want to use Plotly (or any HTML widgets) with Jekyll or GitHub Pages. Sure, there are ways you can do it, but they’re enormously hacky and would lead to an insane posting workflow. In this post, I will show you how to do it the right way.

Everbody else is wrong

~~UPDATE: Including me, evidently! See the very end of this post!~~

Yeah, you heard it. There are numerous blog posts and tidbits out there about using Plotly and HTML widgets with Jekyll, and you should resent every single one of them for being hacky as hell. Let’s go through a few:

- There’s this post by Saul Cruz wants you to do a two-step process where you first knit a file from R Markdown to HTML (individually) and then have another Markdown file load that file.

- There’s a post by Ryan Kuhn that basically suggests writing everything in HTML rather than Markdown, essentially defeating the point of even using Markdown.

- There’s this relatively advanced post by Gervasio Marchand that advocates doing something a little like what Saul suggested, but in a much friendlier, well-thought-out way. Still needleslly complicated though.

So yeah, but nah. I’m here to give you the easy, super-sexy way.

So what’s the problem again?

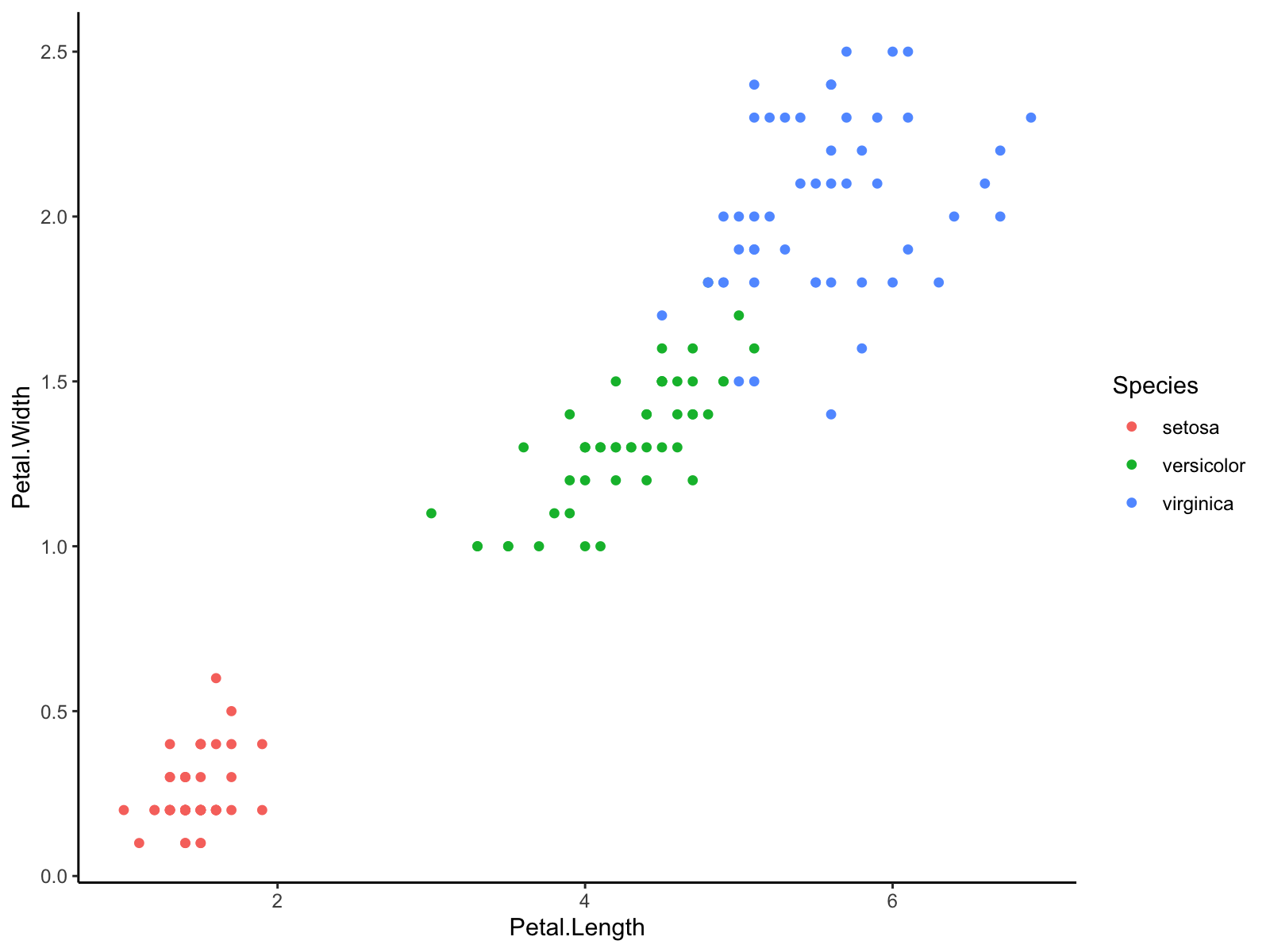

Oh yeah. Let’s get to that. First, let’s make an example ggplot, which works fine in R Markdown -> Jekyll.

library(ggplot2)

library(plotly)

# Make a super simple plot

p <- iris %>%

ggplot(aes(Petal.Length, Petal.Width, color=Species)) +

geom_point()

p

This is a normal ggplot plot, booooring

Now let’s use the ggplotly() function from the plotly package to convert the ggplot into a plotly plot:

# Convert it into a plotly plot

p <- ggplotly(p)

p## PhantomJS not found. You can install it with webshot::install_phantomjs(). If it is installed, please make sure the phantomjs executable can be found via the PATH variable.## Warning in normalizePath(f2): path[1]="webshotafdc31bcc3ea.png": No such file or

## directory## Warning in file(con, "rb"): cannot open file 'webshotafdc31bcc3ea.png': No such

## file or directory## Error in file(con, "rb"): cannot open the connectionOops!

It turns out that when knitr sees that you’re trying to use an HTML widget in a non-HTML output, it actually tries to open it with a web browser, take a screenshot of it with webshot, and then use that. I don’t have a necessary component of that package installed, so it throws an error. Even if it had used a picture, that’s not what we want it to do!

The basic solution

After digging around in the source code from a few packages (what ended up helping the most was the saveWidget() function from the htmlwidgets package), I finally got a grip on what was up. A plotly plot has two major components to it: the HTML that instantiates it, and the Javascript that makes it run.

The HTML

Getting the HTML wasn’t that hard, you can do something like the following in a normal R chunk:

render_plotly_html <- function(p) {

p %>%

plotly::as_widget() %>%

list() %>%

htmltools::tagList()

}Unfortunately, you’ll just end up with an empty place where the plot should be. You still need the Javascript. And that’s definitely the more annoying part.

The Javascript

Normally, the Javascript used to power HTML widgets and plotly plots is already saved in these packages on your computer. When you view the plots from, say, RStudio, it just adds HTML elements that load the scripts in from where they are on your computer, something like <script scr="path-to-script"></script>.

If you want to save a widget and share it with a friend (who doesn’t have the same Javascript files as you) htmlwidgets::saveWidget() will let you essentially smush all the disparate Javascript files so that they’re hardcoded into the HTML file, along with the data, and saves that.

A (bad) first step

And my first attempt at solving this problem was to make code that would basically do just that—automatically save each plotly widget as a standalone HTML file, and load it in through an <iframe> element. But that’s definitely not the ideal situation: you have to redundantly save Javascript dependencies (and load them), and the iframe looks ugly and makes you have to do scrolling stuff.

After really unspooling the saveWidget() source code, I had a better understanding of how dependencies were being handled, and I noticed that when you didn’t smush all the Javascript files into a standalone HTML file, it would “uproot” all the dependencies, copy them to a specified folder, and add them in to the HTML as links. I made my own version:

get_deps <- function(

widget, # The widget in question

postdir, # The path to the posts' content data

basedir, # The base directory of my GH Pages Jekyll repo

libdirname = "js_files/" # A subdirectory for the JS files

) {

libdir <- paste0(postdir, libdirname)

dir.create(libdir, showWarnings = FALSE, recursive = TRUE)

# This gets the dependencies from the widget

deps <- htmltools::renderTags(widget)$dependencies %>%

# For every dependency...

lapply(function(dep) {

# Copy it to the post's directory

htmltools::copyDependencyToDir(dep, libdir, FALSE) %>%

# Adjust it so that the path is relative

htmltools::makeDependencyRelative(basedir, FALSE)

})

}

# Turns the dependencies into HTML

render_deps <- function(deps) {

deps %>%

# Turns the deps into HTML

htmltools::renderDependencies(

# See explanation in text below

hrefFilter = function(x) paste0("/",x)) %>%

# Helps preserve the HTML just in case

htmltools::htmlPreserve()

}Let me explain that “postdir” and “basedir” stuff, the “postdir” is the directory that corresponds to the posts’ _posts/ subdirectory, or wherever you want to keep its automatically generated content, like plot images. The “basedir” variable needs to be supplied because you need to know where the actual post itself is going to be in order to make the links right. What these variables are will totally depend on your setup and how you organize your files, but should be easy to tweak.

I was able to add them as default knitr variables by adding them into my build.R file as plotly.savepath and proj.basedir via knitr::opts_chunk$set().

Notice, however, the hrefFilter function in renderDependencies. I noticed that the output of my dependencies, after I made them relative, started like, <script src="_posts/..., which didn’t actually work. I needed to add an extra slash in front of the relative path for it to work (i.e., <script src="/_posts/...). The hrefFilter argument is a function that puts that finishing touch on.

Anyway, I could now generate the correct HTML links for the dependencies for each plotly plot, doing something like:

HTML <- p %>%

get_deps(

postdir="~/burchill.github.io/_posts/figures/generated/source/x2020-04-04-plotly_with_jekyll/",

basedir="~/burchill.github.io/") %>%

render_deps()In order to get knitr to render the HTML properly though, I had to make the chunk knew to not mess with the output, setting the results parameter to "asis".

```{r, results="asis"}

cat(HTML)

render_plotly_html(p)

```Unfortunately, this meant either redundantly adding <script> HTML elements every time you wanted to display a widget, or hoping that every widget has the same dependencies.1 A “real” right way would only save/load the minimal amount of Javascript files the minimal number of times.

But that would mean collecting all the dependencies, and only rendering them at the end. Can we do that?

Yes.

Function factories and R environments

There are a number of ways you could imagine counting and accumulating all the Javascript dependencies: you could use global variables, you could push the data into knitr variables, etc. I first thought about just using global variables, but I knew that would become messy and error-prone, especially if I had to continue the practice across many different posts.

I’m not going to get into all the nitty-gritty details here, but I decided to use something called a “function factory”, that is, a function that returns other functions. The way R works is that each function call makes its own mini-environment, both when it is called and when it is defined. Look at the inner_fn in the code below: it is defined such that the counter variable it uses comes from the environment above it—one that is created when function_factory() is called.

function_factory <- function() {

counter <- 0

inner_fn <- function() {

print(counter)

# The `<<-` does assignment for variables in higher environments

counter <<- counter + 1

}

return(inner_fn)

}

fn <- function_factory()The environment that the inner_fn is created in essentially “travels with” the function, and the <<- operator lets inner_fn change variables in that environment. It has become a “stateful” function, in that it has a state associated with it (the state that holds counter). See how it keeps track of counter each time it is called:

fn()## [1] 0fn()## [1] 1fn()## [1] 2I figured I could create a stateful function for displaying HTML widgets, that keeps track of all the dependencies of the widgets it displays, accumulating them as it displays them.

Something like:

plotly_collector_maker <- function() {

deps <- list()

function(p=NULL) {

# If you don't give it a plot to take dependencies from,

# it returns the unique set

if (!is.null(p)) {

deps <<- append(deps, htmltools::renderTags(p)$dependencies)

invisible(NULL)

} else {

unique(deps)

}

}

}

plotly_collector <- plotly_collector_maker()

plotly_collector(p)I could go around using plotly_collector() to get all the dependencies, and I could then add a code block at the end that would turn them into the right HTML and have that load the Javascript.

But I could do even better than that. I wanted to make it so that it would automatically load the JS dependencies for me.

Automating the final JS loading

My first move was to see if I could programmatically create a chunk at the end of the document, and put the code in there. knitr is incredibly powerful, so that’s not out of the question. Unfortunately, I didn’t find a way to do that without some very hacky workarounds. But After immersing myself in knitr long enough, I realized I could access the last chunk in the document by using knitr::all_labels(), which would return me the labels of each chunk, in order of appearance.

Then, I could make a knitr hook would check every chunk if its label matched the label of the last chunk. I could then have it spit out the HTML, after it evaluated the last chunk.

# Get the last label

# My cringey `._` naming is because I want to avoid

# common global variable names

._plotly_last_label <- tail(knitr::all_labels(), n=1)[[1]]

# Make a hook that, if it's after the last chunk,

# Spits out the dependencies

knitr::knit_hooks$set(._plotly_checker =

function(before, options) {

if (options$label == ._plotly_last_label & !before)

# Remember, plotly_collector() returns

# the collected dependencies

render_deps(plotly_collector())

})

# Sets the options for every chunk so the hook will be run on them

knitr::opts_chunk$set(._plotly_checker = TRUE)The cool thing about returning strings before and after code chunks (i.e., the output of the ._plotly_checker function) is that you don’t need to have the results="asis"—they’re automatically treated “as-is”, regardless of how the output for that chunk is treated.

But even this is still not clean enough. Even though I named the global variables names that no one in their right mine could accidentally write over, they’re still a bunch of gloval variables lying all gross everywhere, eww so gross.

In order to make things “cleaner”, I decided I could make a “multi-function factory” that would create objects that had multiple stateful functions that all referred to the same state.2 My idea was that I could use the same object to give me both an automated hook function and the plotting function. This is what it would be conceptually:

plotly_obj_maker <- function() {

deps <- list()

hook_fn <- function(before, options) {...}

plot_fn <- function(p) {...}

# I didn't really use the get/set fns, they just show

# how analogous this system is to a Python class

set_deps <- function(newdeps) deps <<- newdeps

get_deps <- function() return(deps)

list(

hook=hook_fn, plot=plot_fn,

set_deps=set_deps, get_deps=get_deps

)

}

plotly_obj <- plotly_obj_maker()

# You can set the hook...

knitr::knit_hooks$set(._plotly_checker = plotly_obj$hook)

# ...and plot with a single function

plotly_obj$plot(p)Putting it all together

I eventually decided that the only function I really needed to surface was the plotting function—everything else could be taken care of behind the scenes, without really reducing important use cases. I boiled it down to the following:

plotly_manager <- function(

postdir = knitr::opts_chunk$get("plotly.savepath"),

basedir = knitr::opts_chunk$get("proj.basedir"),

libdirname = "js_files/",

hrefFilter = function(x) paste0("/", x)) {

last_label <- tail(knitr::all_labels(), n=1)[[1]]

deps <- list()

libdir <- paste0(postdir, libdirname)

render_deps <- function(l) {

if (length(l) > 0)

dir.create(libdir, showWarnings = FALSE, recursive = TRUE)

l <- lapply(unique(l), function(dep) {

dep <- htmltools::copyDependencyToDir(dep, libdir, FALSE)

dep <- htmltools::makeDependencyRelative(dep, basedir, FALSE)

dep } )

l <- htmltools::renderDependencies(l, hrefFilter=hrefFilter)

htmltools::htmlPreserve(l)

}

add_deps_from_plot <- function(p) {

deps <<- append(deps, htmltools::renderTags(p)$dependencies)

}

hook <- function(before, options) {

if (options$label == last_label & !before)

render_deps(deps)

}

plot_plotly <- function(p) {

add_deps_from_plot(p)

htmltools::tagList(list(plotly::as_widget(p)))

}

knitr::knit_hooks$set(._plotly_checker = hook)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(._plotly_checker = TRUE)

plot_plotly

}If I include this single function in a source file or in an early chunk, all I have to do is the following to get a plotting function that will automatically collect all the dependencies, automatically save the right dependencies to the post’s generated source directory, and automatically add the minimal amount of dependencies at the end of the last chunk. All you have to do is:

plot_plotly <- plotly_manager()And then you can use plot_plotly() anywhere to use any plotly plot you want, whenever:

plot_plotly(p)Essentially flawless.

Addendum

I actually wanted to go even further than this. Normally, as far as I knew, when you just return a object visibly in R, it automatically prints it. For example, when you save a plot to p and enter p in the console by itself, it prints out the object.

You can actually change how something is printed out in R by making a print.<class> function—for example, ggplot2 uses the ggplot2:::print.ggplot() function so that when you return a ggplot, it displays the plot.

In a simpler world, I could have just replaced the "plotly" class print function,

print.plotly <- plot_plotlyand you wouldn’t have to even remember to call plot_plotly() to use plotly plots. And, if you do the above and call print(p), it works! The only issue is, if you just do:

pknitr defaults to its bad webshot behavior, evidently bypassing the print() function somehow. If you know how to get around this, please contact me on Twitter or drop me a comment below!

UPDATE! (2020-06-07)

To get straight to the point, I finally learned how to do what I described in the addendum above, and also realized all my code is reinventing the wheel. For a cleaner, better, and more correct version of this code, check out my new post here!

Source Code:

This is the final version of the code I made for this post.

This is the better, improved version of the final code I discuss in my new post.

Footnotes:

-

Technically, the code I have here probably won’t work out of the box with other widgets, since the way I get the plotly HTML is specific to plotly. But it would be trivial to add something that would work with other HTML widgets, and if I ever use them, I’ll change that bit. ↩

-

Notice that this basically is an object-oriented class. ↩